When I talk to my friends and family about mountain biking, two things pop into their mind. The first of which being the bike itself, they usually picture a downhill bike of sorts with large, chunky wheels, a coil sprung rear shock, and a frame that looks like something NASA took 20 years to design. The next thing they think about, and is often what they ask about, is the accidents I’ve had and the scars I’ve accumulated. This picture sums up most people’s thoughts and even what I thought true mountain biking would look like when I started riding the Mongoose on my local blue trail:

Any sport, whether contact sport or non-contact; team or individual; or water, land or air based; all carry some risk to participating in it. I was once a competitive swimmer and even though people within the club had years of experience and could swim across the Pacific ocean if they dared to, all it took was a cramp mid race or one bad breath, and drowning became an immediate concern. Any sport I participated in for competitive or social reasons before mountain biking all carried some risk, and at times I never acknowledged the risk until it was happening.

Because I began my course in radiography before I took mountain biking seriously as a sport, when I began riding at the local trail center I became curious as to the types of injuries sustained by riders. So I did some casual research to pass the time, learnt more about radiography, and stumbled across some pretty major conclusions about how to prevent these injuries and what causes them in the first place.

Even though this is a Rider File and isn’t aimed squarely at life advice, this is a lot to do with radiography and mountain biking. If you are interested in becoming a mountain biker or an amateur like myself, then seriously consider some of the points about to be made.

Most of my conclusions are based on Mountain Biking Injuries in Children and Adolescents by Aleman and Myers. If you want to read the full journal article, ask your local library or online resource if they have it. There were a few other journal articles and blog posts that I read alongside this, but they pointed to a few of the same conclusions.

1. Skill and Experience

The journal article was determined in stating that one of the primary causes, if not the main cause, of mountain biking injuries was down to the rider’s skill level and experience on a mountain bike and on a mountain bike trail. While a helmet and proper fitting shoes do go a long way in lowering the risk of accidents and injuries, this takes aim at what is causing the accident.

As I have talked about in my first blog post, skill is developed and appreciated through the reflective cycle for learning, and as a mountain biker it is important to know where you are in terms of skill progression and what obstacles you can take on. The skills you have developed are a major factor in determining how prone you are to accidents. Knowing specific techniques such as launching your bike and landing a jump safely, guiding your handlebars between narrow gaps, and how to navigate a rock garden at speed can literally be the difference between a hospital trip and moving onto the next section of track. Some of these skills can be learned through a few scrapes and bruises, but once you move up into major gap jumps, high speed downhill manoeuvres and skinny sections with a long fall; trying these for your first time without any prior training becomes very risky. Depending on what obstacle you are taking on, the safety gear you have on and your relative experience in mountain biking, a range of injuries can occur from lack of skill. Sprained ankles, broken wrists, fractured necks, punctured lungs, and everything in between. The journal articles weren’t specific to which obstacles cause which injuries, and what skills best prevent certain injuries; but with so many factors in play such as bike dimensions, speed when approaching the obstacle, rider weight, rider reaction time, where the rider falls, what surface they fall onto and so on, a lot of injuries can occur if the factors are unfavourable.

The other aspect of this is experience. Unlike developed skills which can be learnt in a backyard, on a skills park, or by riding variations of obstacles around you; experience is a bit of how much time you have spent on your bike on trails of a particular build, and how well you understand the sport as a whole. If you talk to the guys at your local bike store, check out the bikes lapping it at your local trail centre, or look at GMBN’s “What Mountain Bike Should You Choose For Your Riding Discipline?” you begin to realise that not all bikes are built equal and for the same type of riding. While there is no harm in riding a downhill racer along a flat, green trail, you are more than likely to have a major accident if you ride a $100 department store bike down a black grade trail for the first time. If you are mountain biking, you need to build up your experience and skills on a well-built and serviced bike if you want to reduce your risk of accidents. The journal article also points to “unrealistic assessment of actual ability” and I agree with this from first hand experience. This is “unconsciously incompetent” exactly, where you believe yourself to be capable of a task but when you attempt it you fail. I was fortunate enough my first time riding a blue course that I didn’t break any bones or ruin my bike, but had it been a different trail or even a black grade; the end result would have been a lot worse.

So as a rider, recognise what your bike can realistically do, what you are capable of in terms of your developed skills (I don’t know how to jump gaps, so I take available B-lines) and have an idea of what the trail has in terms of obstacles before you set off. There are professionals in certain disciplines, because they know what they can do the best with a specific bike and have the skills.

2. Equipment

Need this point need further elaboration? A $100 dualie is not built for hard core courses. It has about 20mm of travel, so it can barely take a speed bump; the pedals are made of the same plastic water bottles are made of, so a single pedal strike at speed will snap them in half; and the brake pads will be cooked and left shredded after the first few metres of the course. Quality components will really save you in this sport. The journal article emphasises that handle bars, suspension components, helmets and proper servicing are key in reducing injuries and minimising the impact of injuries.

Handle bars as an equipment issue was puzzling at first glance, but reading further into it made sense. Straight on, a handle bar is just a long bit of metal (or carbon fibre if you’re fancy like that) and only possess a danger to those coming at you. The worst thing to happen in terms of length of a handle bar to the rider is greater risk of hitting trees and obstacles as you ride and crashing that way. Understandable.

But look at the handle bars from an end point, and what you have is a tiny surface area of a tough material. If you were to fall on that with significant speed or force, it will spear you and cause major damage. It gets even worse when you don’t have grips properly mounted to the ends, and the handle bars can cause even more damage with the exposed ends. The danger posed is abdominal trauma, meaning that in a crash the handle bar end hits the rider in the guts causing damage to the internal organs or to the skin. While riders can’t exactly duct tape big, fluffy pillows on the ends of their handle bars, having proper grips that are secured and have sealed end caps can reduce damage in a crash.

Suspension made the most sense, and was what I thought would be the primary equipment issue. I’ve talked about suspension and travel briefly in the last Rider File so I’ll skip the lecture. While there isn’t a problem in too much travel in the front fork or the rear suspension (if you’re on a dualie) aside from not using its full potential, there is a major issue in not having enough travel when taking on larger impacts. With downhill racing specifically having long travel, triple crown forks to allow for large impact absorption and dampening from big jumps and technical features; it is impossible to expect the same out of a cheap department store bike with a front fork which clearly says “Not for mountain biking”. For something that is marketed as a “mountain bike”, the manufacturer even says not to use it for mountain bike riding right on front fork, says a lot about advertising huh? Having the wrong fork for the wrong discipline will result in significant injury and/or suspension failure. When the fork bottoms out on impact but you still have forward and downward momentum, your arms are going to receive the remaining force which may fracture your wrists or injure your shoulders, or you will go over the bars and injure yourself hitting the ground. If you know your bike well enough in terms of suspension and have developed your skills to take on certain obstacles, then any quality suspension will do. But over-estimating your suspension, or riding on inferior quality components from department stores or low end brands will increase your risk of injuring yourself on the trails.

With suspension cushioning the impact of landing, the better your suspension is the more it protects your joints from injury. The front fork reduces the shock to your wrists, elbows, shoulders, back and hips; while a rear shock absorber reduces impact to the ankles, knees, hips and back. Having these components won’t negate the impact to these joints, but risk of joint pain and sustained injuries is reduced with better quality components which are tuned correctly.

Wearing a helmet in mountain biking seems obvious. Most people envision wearing a full face motor-cross helmet like the image above. But the journal article states that most people who sustained head injuries were either wearing an inferior quality helmet or no helmet at all. I have seen people on trails not wearing a helmet and it makes me furious. While they believe that they have amazing skills and have probably never had a crash in their riding life, all it takes is one wrong wheel turn, a brake lock up or a lapse in attention to bring their head smacking into the ground. The other issue is inferior quality helmets. Sure a helmet looks like a helmet, but the materials used in cheaper helmets do not absorb force well, are more prone to breaking when struck, and thus not protect the brain and face from injury.

Not all head injuries come in the form of skull fractures or broken noses, if the brain rattles about inside the skull enough, life threatening complications can ensue. So do not skip out on buying a good quality helmet, it may be the thing that saves your life in a crash.

Proper servicing in preventing injuries comes down to the simple fact you don’t want your bike to fall to bits on a ride. A few loose bolts in the head set might mean your handle bar stem comes loose and you lose control. Hydraulic brakes that haven’t been bled and maintained might result in loss of braking power. Suspension without adequate lubrication might lead to stiction, seizing and eventual lock up at the worst time. Proper servicing and maintenance can prevent a myriad of issues which further lead to potential injury. Learning proper bike maintenance or taking your bike into a qualified bike mechanic has the potential to reduce injuries.

If you buy a bike from a trusted bike store, with the intent on a specific discipline, buy a good quality helmet and take it back in for servicing when they ask (some even give you a free service within 3 months of purchase), you can reduce your risk of injury.

3. The Trail

The point raised is not to blame the trails for being too difficult, but that riders might be ill-informed when attempting new trails or unexpected trail changes have occurred.

After my first attempt at mountain biking on the local blue trail, every trail center or track I explore, I will try to get a map to know where I’m going and what grade the trails are, and try to get some info on the features from the locals if possible. If I’m riding blind without a map, I go at a reasonable pace so I can stop when needed to assess obstacles. If I know what obstacles there are and if I have the skills to take them on, I am actively reducing my risk of injury before stepping onto the trail. Knowing the differences between green, blue, black, red and double black trails can influence your chances of success and failure when riding.

Unexpected trail changes is the other side to trail-related injuries. Severe weather events, poor maintenance, vandalism by both mountain bikers and general public, natural phenomena such as falling trees, and erosion can all unexpectedly change the trail for regular users and for new users. Type of injury and the severity of the injury are dependent upon rider skill, the speed upon approaching the trail change, and the condition of the bike. But unexpected is unexpected, so there is no way of knowing what injuries will arise. The best way to prevent injuries from this is to react as quickly and as safely as you can, and report damage to the local club or maintenance crew so no further injuries can occur.

4. Speed

As a stand alone concept, speed doesn’t appear to be difficult to understand. The faster you are going, the harder you’ll hit the object and fall. Not always true.

Some obstacles such as rock gardens favour higher, controlled speeds since the wheels can skip over smaller gaps and not become stuck. Going too fast into a flat corner may result in under-steer and result in the rider going off track. Speed is relative to the obstacle at hand. But speed is crucial in jumping, and committing to a jump by having enough take off speed is key to survival. These diagrams, intricately drawn with Snapchat, will help demonstrate my point:

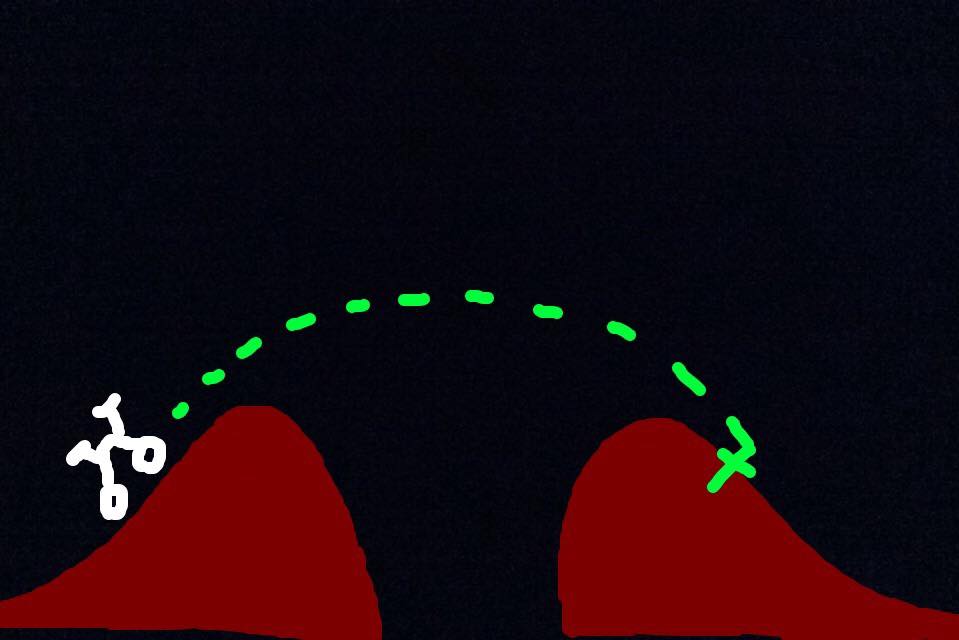

This diagram demonstrates the ideal jump (even if the bike looks like a 5 year old designed it) where an ideal take off speed is used and results in an ideal landing. Committing the right amount of speed means you clear the top of the landing and the wheels touch ground on a tangent, so you’re rolling with the down slope rather than impacting straight down. This is what dirt jumpers dream of achieving as it helps maintain speed for the next jump and reduces the impact to the body and bike.

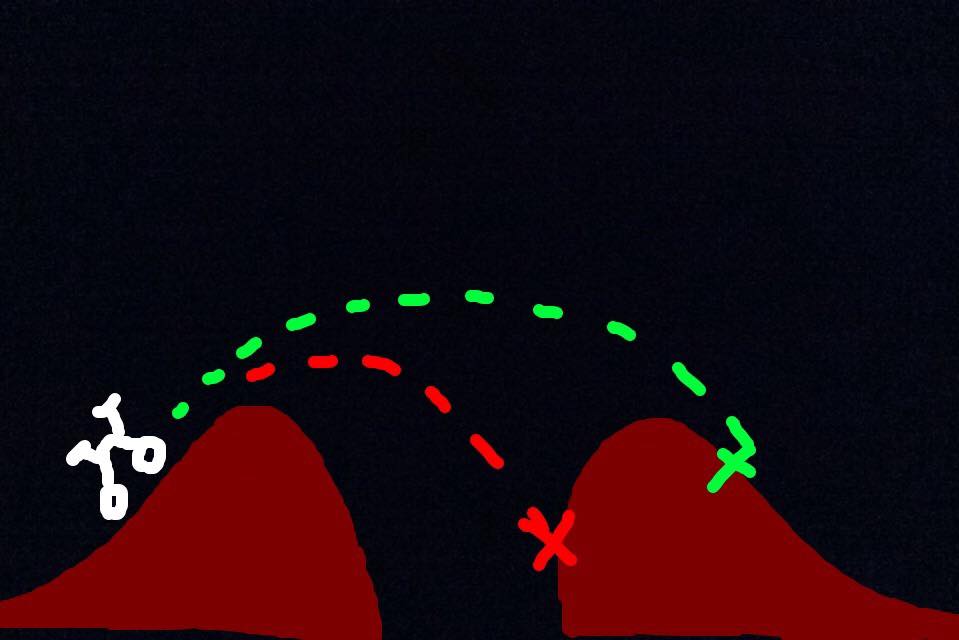

This diagram demonstrates the worst possible outcome and is the reason why I haven’t attempted jumping yet. By not committing enough speed to the take off or by having a poor launching technique, the bike has a shorter arch and hits the jump, resulting in significant damage to the rider and bike. Not having enough speed and backing out is counter-intuitive since slowing down reduces your arch and prevents you from landing. To prevent injuries from these kinds of accidents, you actually need more speed or a better launch technique. So going slow isn’t always the way. But what about too fast?

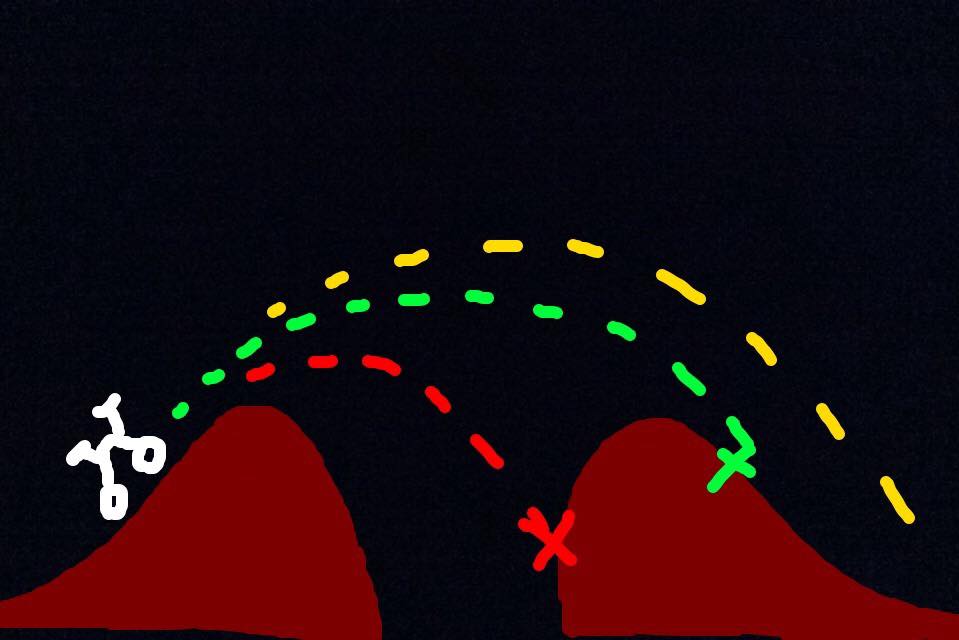

Going too fast may not be the worst scenario. While you have cleared the top of the landing, the issue is that your arch becomes steeper as you travel further and therefore you will experience more downward impact than forward momentum. You will most likely hit the ground harder and could potentially be thrown off your bike on impact. You might also overshoot a turn or plow straight into the next technical obstacles, both most likely resulting in a crash. Too fast doesn’t necessarily mean you will crash, but it has an increased risk of injury than hitting the jump at the right speed.

Speed is a difficult factor to understand in terms of injuries. While a greater crash velocity will result in a higher forces experienced and increased chances of injury, some obstacles do require a significant amount of speed in order to successfully clear them. To combat speed related injuries comes down to experience and skill level; knowing the trail and it’s obstacles; and having a well serviced bike that can reliably take on the terrain.

There were a few more points made by the main journal article and the other sources, but those four were concurrent amongst them and provide valuable advice on how to minimise injuries within the sport.

The journal articles and blog posts made me realise how complex and dangerous mountain biking can be if you don’t adopt the right attitude and back yourself up with good quality equipment and skills training. I have been in accidents, some minor that I walked away with scraped skin and chipped paint work, other times I broke or the bike broke. And in every one of those accidents, I think back and realise that one or more of the four factors were responsible for the crash.

Mountain biking is not about riding something that resembles a “mountain bike”, riding it fast on a dirt trail you found, and having a “wicked” crash. Mountain biking should be taken seriously by having the right skills, gear, attitude and trail knowledge to happily and safely enjoy a trail that has been constructed by a dedicated community or organisation. Mountain biking is risky, but if you want to be seen as a professional or at least a decent rider, it’s about riding with speed, skill and safety; and not how hard you crash into a rock.

This sport is one of the greatest thanks to the wide variety of equipment available, sporting grounds on offer and the flexibility to ride obstacles. So participate in one of the world’s greatest sports safely, not hap-hazardly?

One comment